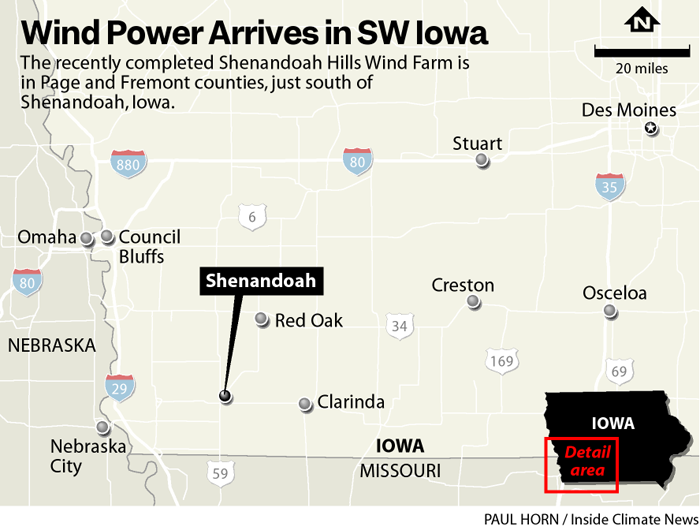

SHENANDOAH, Iowa—First viewed from a pickup truck driving south on U.S. 59, the wind turbines seem small and delicate.

The newly constructed wind farm is a matter of pride for Gregg Connell, the man behind the wheel of the truck. He is a former two-term mayor of this southwestern Iowa city and an official with the local chamber of commerce.

The turbines are “beautiful,” Connell said, looking out the driver’s side window. “You’re capturing energy, you’re helping the environment.”

But the sight of a new wind farm is increasingly rare, even in Iowa, a state that trails only Texas in electricity production from wind.

Wind energy development has all but ground to a halt in the face of community opposition, a phaseout of federal tax credits and the Trump administration’s actions to slow the approval of federal permits.

Some of the administration’s most notable moves on wind power have been attacks on offshore development, including a stop-work order in December that halted construction on five projects. But land-based wind projects—often described in the industry as “onshore wind”—are a much larger contributor to the nation’s electricity supply and are struggling to make even modest gains. Without robust growth in onshore wind, the United States will be severely limited in its ability to build enough power-generation capacity to meet rising demand and combat climate change.

One of Iowa’s few new developments, the Shenandoah Hills Wind Farm, illustrates what it takes to build in the current political and regulatory environment.

The developer, Chicago-based Invenergy, faced years of blowback from residents who raised concerns about damage to the visual landscape along with concerns about potential harm to human and animal health and effects on property values. The opposition campaign dragged on into court cases and led to one county supervisor losing his re-election bid.

Though controversial, Shenandoah Hills still had the advantage of obtaining all of its federal permits before the Trump administration returned to office in January and began using federal agencies to slow or halt new projects.

If the Shenandoah Hills ordeal is what success looks like for the wind industry, then it’s understandable that investors, developers and others see few reasons to pursue new projects.

“U.S. onshore wind is in its weakest shape in about a decade, not because the technology has stopped being competitive, but because the policy and, to an extent, the macro-environment have turned sharply against it,” said Atin Jain, an energy analyst for the research firm BloombergNEF, in an email.

In 2024, the most recent full year for which data is available, wind energy produced 7.7 percent of the nation’s electricity, more than any other renewable source, according to the Energy Information Administration. Since the country has only three operational offshore wind farms, onshore wind accounts for nearly all of this production.

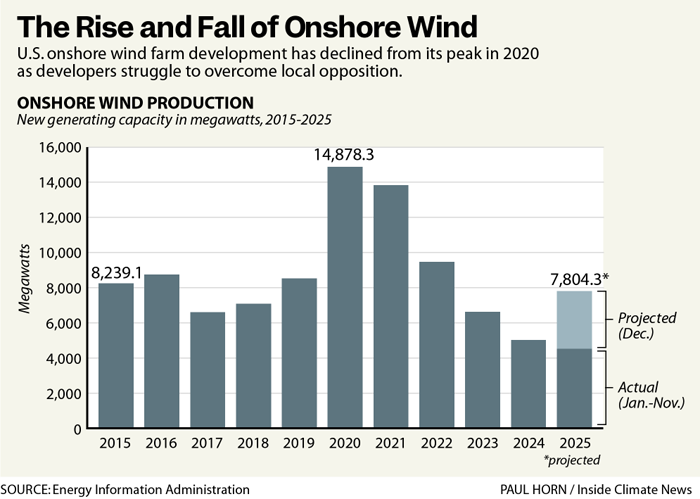

New projects peaked in 2020 when 14,878 megawatts of onshore wind farms came online in the United States, according to the EIA. This number has decreased steadily since then, bottoming out at 5,026 megawatts in 2024.

The industry had a slight rebound in 2025, with 7,804 new megawatts of capacity—including completed projects and those that were projected to be operational by Dec. 31—and will grow more in 2026, with 10,044 megawatts listed by EIA as planned for completion.

After that, things are likely to get much worse. Developers and analysts expect a drop-off in 2027 and beyond, when the current chill in development stemming from the Trump administration’s actions will lead to fewer completed projects.

Meanwhile, electricity demand is soaring as utilities and grid operators determine how to meet the needs of large users such as AI data centers.

There is a disconnect in the market when demand is surging while wind power development is slowing, a situation that bodes poorly for the future of clean energy in the U.S., said Michael Thomas, CEO of Cleanview, a market intelligence platform focused on power plants and data centers.

“The decline in wind energy development is one of the trends that I’m most concerned about when it comes to climate progress in the United States,” Thomas said in an email. “I’m not aware of a single model that shows us meeting our climate targets or avoiding significant warming without a huge buildout out of wind power.”

A City Divided

Connell, 76, parked his truck on the gravel lot that the wind farm’s construction crew has used as a staging ground for the past year. Workers installed the last of 54 turbines in November, bringing the total generating capacity to 214 megawatts.

Acting as a tour guide for two reporters, Connell had spent much of the day discussing his work as mayor and now as executive vice president of the chamber of commerce to attract jobs and investment to Shenandoah.

A city of about 4,900 residents, Shenandoah was the childhood home of the Everly Brothers, the musical duo behind hits such as “Wake Up Little Susie.” The main street has a vitality that many other cities of this size would envy, with a first-run movie theater and a recently renovated mill that now hosts an indoor farmers market.

Still, such vibrance is a challenge to maintain.

The median age in Page County, which includes much of Shenandoah, is 45 years, the 12th highest of Iowa’s 99 counties. To grow and prosper, the community needs to attract new residents, and, to do so, it needs to maintain and expand a tax base that can support schools and government services.

“We need more young people,” Connell said.

The Shenandoah Hills wind farm is one of the largest investments in the county’s history. Payments to landowners and local governments are projected to total $234 million over the life of the project, according to Invenergy.

For context, the Shenandoah school district has an annual budget of $28.4 million, with $6.2 million from local property taxes. The wind farm is expected to generate an additional $1.3 million in property taxes annually for the district, based on a 2022 estimate from a consulting firm on behalf of Invenergy.

Its plans for a wind farm in the area had been underway since the mid-2010s. The company already had the support of landowners willing to lease their property and of government officials who were moving forward with permit approval.

Then, in the late 2010s, something changed. In both Iowa and nationwide, wind energy projects began to face local opposition that was more aggressive and better organized than before.

Some of the shift was due to the boom in wind energy, which had already changed the landscape in parts of Iowa, contributing to backlash from residents who disliked the look of the turbines.

Some of the changing tide was partisan, fueled by the hardening of beliefs that Democrats support renewable energy and Republicans—the large majority in rural Iowa—support fossil fuels. President Donald Trump helped to popularize this view with his use of the unfounded term “wind cancer” and other criticism of wind and solar energy.

The upshot was that the development of Shenandoah Hills turned bitter.

The opposition organized on social media, including a Facebook group, Page County Horizons, which served as a forum to encourage attendance at public meetings and share video clips and articles portraying wind energy as dangerous and unreliable.

Todd Maher, who lives within view of the wind farm, opposed the project and decided in 2022 to run for the county Board of Supervisors because he felt that officials weren’t listening to concerns. He won in the Republican primary, defeating the incumbent, who supported the wind farm, and then ran unopposed in the general election.

“A lot of people want to live where they can see the sunrise and sunset without having to look at a wind turbine,” he said, interviewed on a recent Sunday afternoon.

Maher, 55, lives on an acreage with a donkey, chickens, cats and dogs. He has worked for most of his adult life at the Pella Corp. window plant in Shenandoah.

One of his main concerns with the wind farm was the disconnect he observed between the landowners who would receive lease payments and residents who would actually see the turbines every day. Most of the owners don’t live near the turbines, and many of them don’t live in the county or the state, he said.

This isn’t unusual, with the heirs of farmers and investment companies owning a large share of U.S. farmland. But it’s frustrating, said Maher, that people who live in the area will have their views spoiled while somebody else is paid for the leases.

Once Maher took office, he found it wasn’t easy to stop the project. The board passed a moratorium on wind energy development that was to include Shenandoah Hills. Invenergy responded by suing the county, arguing that the sudden change should require taxpayers to reimburse the company for the money it had already spent.

Legal counsel warned county officials that there was a decent chance of losing in court and then facing a judgement so large that the government might need to file for bankruptcy.

Maher was unwilling to take that risk. In November 2024, he was in the majority in a 2-1 vote to accept a settlement with Invenergy that would allow the project to move forward.

“It was the toughest vote I’ve ever made,” he said. “I lost a lot of friends over it. I lost a lot of people that supported me.”

“Closed for Business”

Iowa, especially its western half, has some of the richest wind resources in the country.

Early developers capitalized on this, with the completion of Storm Lake 1 in northwestern Iowa in 1999, the first wind farm in the state with a capacity exceeding 100 megawatts. By 2010, wind farms were a familiar part of the landscape, with more than 3,500 megawatts of capacity, including some large installations along I-80, the major east-west highway that bisects the state, connecting California to New Jersey.

For years, Iowa’s leadership in wind energy was a point of pride, with the silhouette of a wind turbine appearing on the state’s license plate next to images of city skylines and farm buildings.

Wind power enjoyed bipartisan support in the state, with proponents including Democrats such as former U.S. Sen. Tom Harkin and former Gov. Tom Vilsack, and Republicans such as former Gov. Terry Branstad and U.S. Sen. Chuck Grassley. They viewed wind farms as an opportunity to increase incomes in rural counties.

Their vision paid off. As of 2024, Iowa led the country in the share of electricity produced by wind farms, with 63 percent.

But the era of growth in Iowa’s wind industry is almost certainly nearing its end. Shenandoah Hills was one of just three wind farms to be completed in the state in 2025, and only one was completed in 2024, according to the EIA. The last significant year of development was 2020, when 12 projects went online.

The contraction of the industry is a grave concern for Jeff Danielson, a Democrat who served four terms in the Iowa Senate and now is vice president of advocacy for Clean Grid Alliance, a clean energy business group.

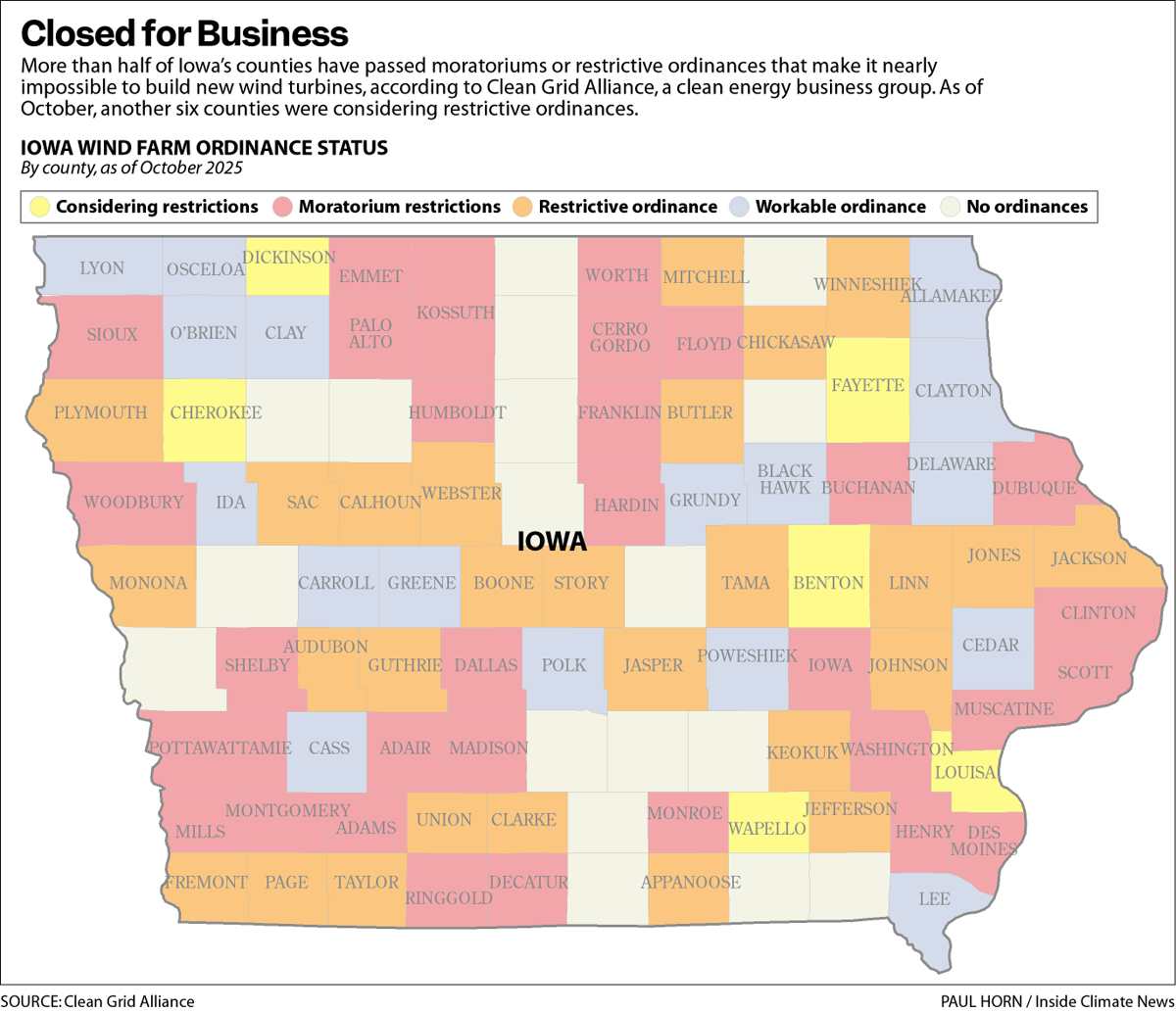

“Iowa is essentially closed for business when it comes to wind development,” he said.

The resistance comes almost entirely from the local level. His organization lists 58 of Iowa’s 99 counties as having rules designed to limit wind power development, including many of the counties with the strongest wind resources.

He described the opposition as formidable in its ability to organize at the local level and then throw out a large number of objections in the hope that one of them will stick. It’s not a fair fight, with one side repeating a litany of claims found on anti-wind websites, and the wind power companies obligated to stick to facts that will stand up in court, said Danielson.

“It’s not even really an adult conversation anymore,” he said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowIf Iowa’s legislature and governor wanted to encourage wind energy development, they could pass a law to expand state authority to approve projects, limiting the ability of local governments to pass restrictions. The state has previously done this on hot-button issues such as regulating large animal feeding operations, but there’s little indication they’ll intervene when it comes to wind.

“One thing you find out about legislators is they like local control when they like it, and they don’t always like it,” said Iowa Rep. Brent Siegrist, a Republican whose district is a short drive from Shenandoah.

Siegrist supports wind energy and thinks it is important for making Iowa an attractive location for providing plentiful, affordable electricity for data centers. But he doesn’t expect any push at the state level to make it easier to build wind farms. Republicans control both chambers of the legislature and the governor’s office.

“I’m not sure that we would step into that,” he said.

Exacerbating Global Roadblocks

If Iowa isn’t building much wind power, it’s a bad sign for the industry as a whole.

But local opposition in rural areas is just one of several obstacles for wind developers.

The passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act in July included a rapid phaseout of the production tax credit, an important federal policy that had helped to encourage development.

Developers are now on a tight deadline. Projects must be completed by the end of 2027 or begin construction by July 4, 2026, to qualify for the tax credit.

Amidst the rush to begin construction, the Trump administration has issued executive orders to slow development of wind and solar. Interior Secretary Doug Burgum has taken additional steps, requiring that he personally sign off on new wind or solar projects subject to his agency’s jurisdiction.

Jain, the BloombergNEF analyst, said the global wind energy market faces challenges tied to local acceptance and slow progress in building enough power lines to serve new projects.

The United States deals with those same problems, as well as the obstacles created by its federal policies.

The U.S. outlook, Jain said, “now looks so much weaker than the global picture.”

Uncertain Ground

In Shenandoah, the wind farm is up and running but the debate over its approval has left scars.

In February 2025, Invenergy sold the project to MidAmerican Energy, Iowa’s largest electricity utility. Invenergy quietly walked away from the wind farm while MidAmerican inherited a community relations crisis.

MidAmerican has attempted to smooth things over, hosting events for landowners and community members and meeting with supervisors and engineers of Page and Fremont counties.

Outside of the two counties, MidAmerican’s publicity for the wind farm has been scant. However, in recent correspondence with Inside Climate News, the company expressed no regrets over its decision to take on the project.

“The Shenandoah Hills wind farm is an economic success story for both Page and Fremont counties,” Geoff Greenwood, media relations manager for MidAmerican, wrote in an email. The company projects paying nearly $87 million to Fremont County and $65 million to Page County in property taxes over the life of the project, said Greenwood.

“Wind energy has helped us create relationships with partner landowners and helps Iowa attract new companies to the state. It also provides direct, long-term economic benefits to our rural areas,” Greenwood added.

But as the very last turbines were erected outside Shenandoah, the atmosphere hardly felt triumphant.

The closest thing to a celebration was a ribbon-cutting held in September 2024 when Invenergy opened an office in downtown Shenandoah to manage the construction and community relations.

Connell, who has been unabashed in his support for the project since the beginning, was one of the people holding the ribbon. But his words that day didn’t feel like a victory lap.

“This has been a difficult project,” he said, quoted by KMA, the local radio station. “There are people that oppose wind, and there are people for wind. But I admire the fact that Invenergy, in my estimation, has taken the high ground on everything.”

The office closed a few months later, around the time of the sale to MidAmerican.

Maher, the county supervisor, wishes the wind farm had never happened. But since it’s here, he is hopeful that he and his neighbors can learn to live with the change.

“Maybe things will not be as bad [as we fear, and] we can find a good common ground to where we can coexist.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,