Lake St. Clair, a heart-shaped lake straddling the border between Michigan and the Canadian province of Ontario, has long supported a busy and reliable “blue economy.” The smallest in the Great Lakes regional chain, the lake attracts thousands of people every year who fish, boat and enjoy its freshwater shoreline and trails.

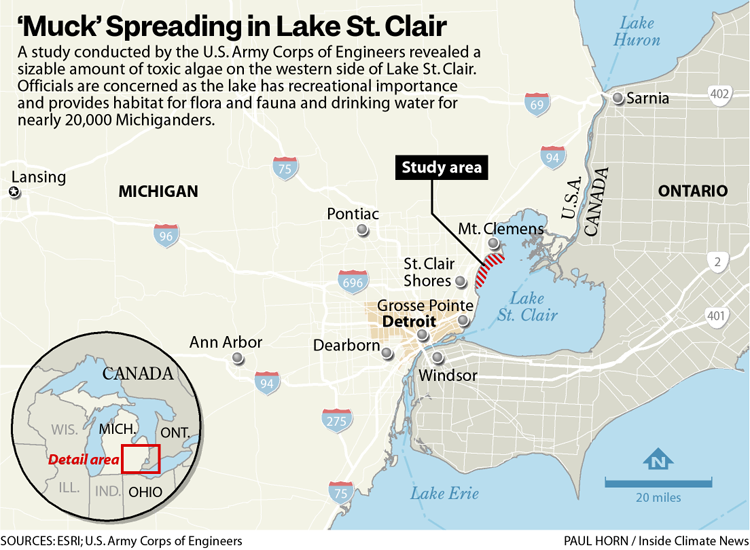

But a bounty of muck—a foul-smelling brown algae blocking lake access in some areas—has been souring the good times on Lake St. Clair. The algae, known as Microseira wollei, will now be targeted in a cleanup devised by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which has been working with scientists and representatives at the local and state level.

“You can dredge this stuff out. The problem is it comes right back,” said Candice Miller, the public works commissioner for Macomb County, Michigan, which borders the lake’s northwestern edge.

“The scope of the issue is large. It’s daunting, but that can’t dissuade you from wanting to do something,” she said. Miller, eager to see state funding back the Corps’ proposed cleanup, described herself as “cautiously optimistic” about the work set to begin next year—in part because residents have made it clear they want the state to do something.

The state’s 2026 budget, which the legislature passed Oct. 3, allocates $800,000 for a three-year “field trial” to test methods of managing the algae.

Residents first noticed brown crud along the edge of the lake over 20 years ago. It turned out to be balls of algae breaking away from thick mats of nutrient-loaded algae growing at the bottom of the lake.

“As it’s decomposing, it definitely looks like mud,” said Cleyo Harris, a fisheries biologist at the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. “Because of the smell, some people thought it was even worse stuff. Some people were worried that it was fecal matter.”

Microseira wollei blooms in waters around the world and can produce toxins and harbor other bacteria, making it potentially harmful to people who come into direct contact with the blooms. Over the years, water treatments have mitigated health risks from Lake St. Clair, which provides potable water for approximately 18,000 people.

Still, the algae has increasingly bothered lakeside residents. Over the past decade, rapid algae growth has meant dredged boat launches can become blocked again in just weeks—a major concern for an economy so tied to the lake.

“It’s a highly utilized resource from a fishing standpoint,” Harris said. “I can’t undersell how important that lake is, and hopefully, we can take some good steps to make sure this problem doesn’t continue to get worse.”

The muck has even bedeviled the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, which had to move its boat launch after repeated small-scale dredging was not enough to clear the clogs or or stop the algae’s relentless spread.

In 2023, Macomb County partnered with the Engineer Research & Development Center—the research arm of the Army Corps of Engineers—to research ways to hinder these pervasive algae blooms. Their collaboration started with a $400,000 two-year contract—jointly funded by Macomb County and the Corps—to research the algae and whether they can remove it.

“It covers a lot more of Lake St. Clair than I think we anticipated,” said Alyssa Eck, lead author of the Army Corps of Engineers’ study.

The Corps researchers found the algae was too widespread to totally eradicate. Instead, they’ll embark on a long-term management strategy, focused on mechanically dredging the lakebed to remove large mats of algae. Depending on their success, they may also douse the M. wollei with algaecide.

The dredging-and-algaecide strategy has worked in other locations afflicted by M. wollei, Eck said. The Alabama Power Company has been successfully managing M. wollei in one of its reservoirs, Lay Lake, for over 20 years.

“There were people who were there at the start of those treatments that said it seemed like you could walk across the mat, which is analogous to some locations in Lake St. Clair,” said Eck, who studied other cases while making a plan for Lake St. Clair.

With funding secured, dredging is set to begin in a few pilot locations around the lake—and residents are eager for work to begin.

“The biggest comment we get is, usually, ‘can you go faster’? Then, ‘can you do something’,” said Brandon Hubbard, a spokesperson for the Army Corps of Engineers’ Detroit District. “There’s just a general concern about getting the shoreline usable.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,