A sprawling winter storm that left hundreds of thousands without power, grounded thousands of flights and disrupted travel across the eastern half of the U.S. could be the first real test of the second Trump administration’s Federal Emergency Management Agency.

The president has said that he wants to eliminate FEMA, and the agency has lost thousands of employees since his second term began. Emergency-management experts have braced for the moment that a weakened FEMA would face a multi-state disaster.

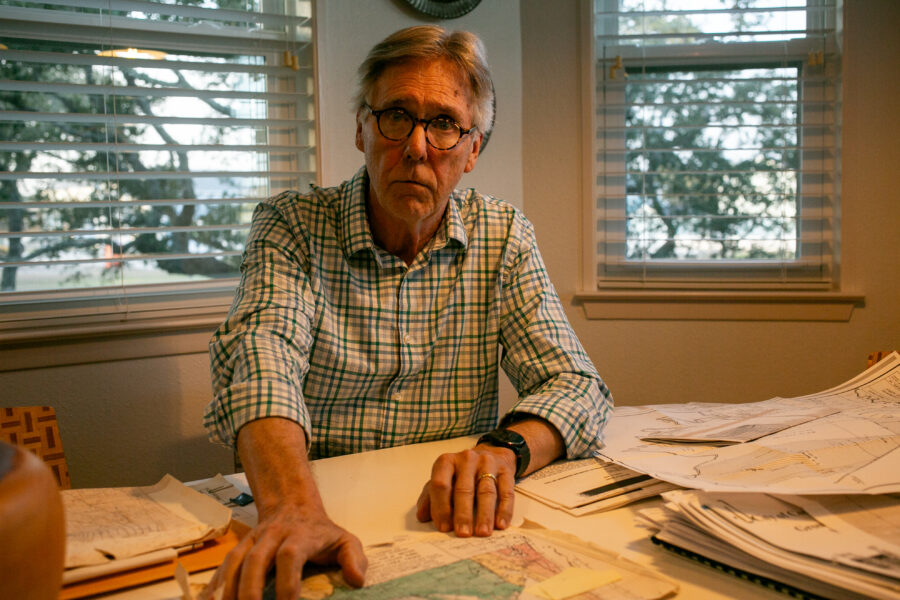

“We’ve been lucky, really, over the last year,” said Alan Gerard, a retired National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration meteorologist who now writes the newsletter Balanced Weather. “We didn’t have any landfalling hurricanes. We haven’t really had a wide-ranging natural disaster-type situation in the last several months.”

FEMA typically plays a key role in coordinating and delivering resources when an emergency hits multiple states at once. “FEMA and the whole federal infrastructure is really critical in terms of organizing big responses like this,” said Mathy Stanislaus, a former assistant administrator for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Land & Emergency Management.

President Donald Trump has so far approved federal disaster declarations for 12 states, mostly in the South, in the wake of the storm.

The Trump administration’s cuts to FEMA come at the same time that climate change is making large-scale weather disasters more likely and more intense, even as the president continues to question the basics of climate science. On Friday, Trump posted on social media about the storm and cold snap, asking followers, “WHATEVER HAPPENED TO GLOBAL WARMING???”

In fact, scientists say, global warming has reshaped the atmospheric engine in ways that can make winter storms and extreme cold outbreaks more disruptive than ever.

Rapid Arctic warming and melting, stronger and more intense ocean heat waves, increased atmospheric moisture and more frequent disruptions of the stratospheric polar vortex are all factors “contributing to the extreme winter weather unfolding across the U.S. this week,” Jennifer Francis, an atmospheric scientist and senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts, said via email.

More than a foot of snow fell across the U.S. from Arkansas to Massachusetts, with some places seeing nearly two feet. Ice blanketed much of the South, bringing down tree limbs and knocking out power from Texas to North Carolina.

At least 20 people were killed during the storm, and thousands are navigating power loss, dangerous travel conditions and freezing temperatures. More than 600,000 homes and businesses were without power as of Monday afternoon.

Emergency management experts and government officials warned that the situation is still unfolding, particularly in Southern states impacted by ice. Falls, traffic accidents, hypothermia and carbon monoxide poisoning are among the possible threats in the storm’s aftermath.

“The danger period is much higher immediately after the storm passes,” said Craig Fugate, a former FEMA administrator.

How Climate Change Reshapes Winter

Scientists agree that human-caused warming has changed the way air and energy move around the planet in complex and interrelated ways that influence outbreaks of extreme winter weather.

The current cold wave is not happening in isolation, but in a fundamentally altered climate system. At a basic level, the oceans are warmer and the atmosphere holds more moisture than 50 or 100 years ago. Both fuel stronger storms, including nor’easters, which have intensified significantly in recent decades, according to a 2024 study.

Nor’easters spin up along the East Coast, drag subtropical moisture from the south and pull frigid polar air from the north. Both their maximum wind speeds and hourly precipitation rates have increased since 1940, said University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann, a co-author of the paper.

That research, he said via email, for the first time was able to quantify the changes. He warned that “more intense storms, with greater amounts of snowfall” are to be expected, even as the planet warms.

“Stronger storms, as they spin, pull up more warm air on one side and pull more cold air down on the other side, so we see both warm and cold temperature extremes associated with them,” he said.

Along with warmer oceans and a wetter atmosphere, global warming has also reduced Arctic sea ice by nearly a third since the 1980s, which is enough to change the path of the jet stream, the wavy, fast-moving river of air that separates cold Arctic air from warmer air to the south.

Extreme cold events are usually linked to big north-south bends in that flow, said Francis, the Woodwell Climate Research Center scientist, who is known for her research on rapid Arctic warming and its influence on mid-latitude weather patterns.

Right now, the jet stream is bulging far north over the western U.S. while plunging deep south over the east, allowing Arctic air to spill unusually far south. The pattern is becoming more common as the Arctic warms faster than the rest of the planet, weakening the temperature contrast that normally keeps the jet stream straighter and faster.

“Big waves like this are more common when the Arctic is unusually warm, and it’s near record-warm right now,” she said. The pattern has been common this winter and likely is linked with a strong and persistent ocean heat wave in the North Pacific, she added.

An ocean heat wave in that area bulges the jet stream north over the West, causing a southward dip downstream, over the central and Eastern U.S., followed by another northward bulge that brought extreme warmth to Greenland.

Adding complexity is the fact that Arctic warming is uneven, said atmospheric scientist Judah Cohen, director of seasonal forecasting at Atmospheric and Environmental Research and a visiting scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Parsons Laboratory. He’s known for his work on how Arctic variability influences winter weather and the polar vortex, a pool of frigid air usually locked high over the Arctic.

Especially intense heating north of Scandinavia ripples the atmosphere in a way that disrupts the polar vortex. When the ripples caused by uneven warming turn into larger waves, they reach the high-altitude polar vortex and distend it, like a soft water balloon.

In that stretched position, Cohen said, the polar vortex pulls extremely cold air from Siberia across the Arctic and into the central and eastern U.S. Because the air travels quickly, it has little time to warm, increasing the likelihood of severe and long-lasting cold outbreaks.

Meanwhile, some areas of the U.S. that rely on snow are increasingly out of luck. While the East shivers, much of the West has been gripped by warm and dry conditions for weeks, with winter snowpack—critical for summer stream flows—near record low in many areas.

A Deep Freeze in the Deep South

Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee were among the states hardest hit during the storm, with more than half a million customers still without power as of Monday morning. Utility companies in Tennessee described “catastrophic damage,” and in Mississippi, one company warned it could be weeks before power was fully restored.

That grim news comes as the region faces extremely low temperatures tonight. These conditions could be dire for some people if they are trapped without power in their homes for an extended period of time.

In Louisiana, at least two people died due to hypothermia in Caddo Parish, according to the state’s Department of Health. The Tennessee Emergency Management Agency confirmed three deaths related to weather conditions in Crockett, Haywood and Obion counties near Memphis.

The mayor of Oxford, Mississippi, Robyn Tannehill, said in an interview with meteorologist Matt Laubhan that the damage in her town was “extensive.”

“It looks like there’s been a tornado on every street in Oxford,” she said. “Trees on houses, trees on cars, trees blocking roadways, trees that have pulled whole power lines down and power poles that have snapped. It is an emergency situation right now.”

Fangs of ice hung from trees and power lines in Tennessee, where Gov. Bill Lee told residents in an online briefing Sunday that the storm was “unusually dangerous in many ways.”

Freezing rain, strong winds and temperatures in the lower single digits “can hamper our ability to respond” amid widespread power outages, said Patrick Sheehan, director of the Tennessee Emergency Management Agency.

“It looks like there’s been a tornado on every street.”

— Robyn Tannehill, mayor of Oxford, Mississippi

Residents in Adamsville, Tennessee, located near the Mississippi border, lost access to running water and won’t get it back until power is restored.

In North Carolina, some of the worst impacts of the storm occurred in the western mountains, which are still recovering from damage Hurricane Helene inflicted in September 2024.

“We are concerned about the double-whammy impact,” Gov. Josh Stein said during an online briefing Saturday. “Any future trees falling will add more fuel on the ground once we get into wildfire season.”

In Mississippi, Gov. Tate Reeves said on Sunday that the situation in the state would get worse before it got better as ice on trees and power lines continued to cause power outages in gusting winds. Reeves said the state was coordinating with FEMA to bring in additional generators and supplies for warming centers, such as cots, water and blankets.

Some people may have difficulty getting to those warming centers. Road travel continues to be impacted across the South, where temperatures are expected to remain at or below freezing throughout Monday.

“As the governor said, we can sum up our road conditions and road travel with one word, and that is, ‘nope,’” said Brad White, the executive director of the Mississippi Department of Transportation. “We would love to see y’all but not zigzagging across three lanes of traffic at 40 miles per hour.”

In Alabama, 27-year-old Morgan Lakesha Hawkins of Birmingham was killed and another person was seriously injured after their vehicle struck a guardrail in nearby Mountain Brook.

The danger for people in the South is not over, especially for those without power. “An extremely cold night is forecast tonight with low temperatures in the single digits,” said Gerard, the meteorologist. “This level of cold is highly unusual, and buildings are not generally built for [it]. The danger of hypothermia and infrastructure damage to things like water pipes and mains is significant.”

“Torturous” Cold in Chicago

The Arctic air brought Chicago its lowest recorded wind chill since 2019, at 36 degrees below zero on Friday, according to the National Weather Service’s local office. Chicago Public Schools closed that day, with the city on an extreme cold watch then and throughout the weekend. NWS warned that just 10 minutes outside could result in frostbite on exposed skin.

Extreme cold poses other serious health hazards, including hypothermia and the exacerbation of chronic conditions. From Thursday through Monday afternoon, 339 patients were seen for cold-exposure injuries at Chicago emergency departments, according to the city’s Department of Public Health.

The number on Saturday alone, 119, was almost four times more than the city expected. Nearly half of the patients were Black, which speaks to the unequal impact of weather hazards.

Cold-related health hazards are most acute for the elderly and those without access to consistent shelter. Rev. Shawna Bowman, executive director of Friendship Community Place, a neighborhood hub in Jefferson Park on the city’s Northwest Side, coordinated with volunteers to keep the space open as a warming center over the weekend and helped unhoused residents find safe places to spend the night.

Bowman said it can be challenging for residents to know what resources are available and to travel to warming centers not in their neighborhood. The Northwest Side has “a real dearth of resources,” they added, and mutual-aid efforts like theirs are working to fill in the gaps.

Early Saturday evening, the community-run center had a handful of visitors, some eating instant ramen to warm up from the cold.

Ivon Ivans sat on a sofa near the entrance, preparing to go to a nearby church with her boyfriend, Miguel Martinez, for the night. Ivans has been homeless for three years and is on the waitlist for housing through the Chicago Housing Authority, she said. Martinez said he has been unhoused for about 20 years.

Ivans said she has several chronic health conditions that are exacerbated by the cold, including cirrhosis of the liver and anemia. Martinez has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that flares up in the winter, making it harder for him to breathe.

“It’s torturous,” Ivans said of the weather.

Across the street from the community center, five people were taking refuge for the night at a police station—all of which are open 24 hours for shelter from the cold.

Yvette Hausman and her fiancé, Nathan Watkins, who are both unhoused, sat on the floor of the station with blankets and some belongings. Hausman said she didn’t know the cold was coming, but that she was grateful for community members who mobilized quickly to provide and spread the word about impromptu warming resources.

“There has been a lot of warming centers that have popped up randomly,” Hausman said. “You just see the community come together.”

“The First Boots on the Ground”

It’s not yet clear how turmoil at FEMA under the Trump administration could be impacting response and recovery for the storm, but experts are concerned that delays in the allocation of funding, leadership upheaval and staffing cuts mean that the agency’s ability to function effectively during and after an emergency has been seriously constrained. FEMA did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“Certainly the dysfunction at FEMA over the past year is affecting any response that happens across the country,” said Samantha Montano, an associate professor of emergency management at Massachusetts Maritime Academy and the author of the book “Disasterology: Dispatches from the Frontlines of the Climate Crisis.”

The Trump administration laid off or forced out more than 2,000 FEMA employees in 2025 and had planned to end the contracts for thousands more this year until Thursday, when the agency paused that effort amid preparation for the winter storm. More than 300 CORE, or Cadre of On-Call Response/Recovery Employees, had already been let go by that point.

CORE workers are critical at FEMA, said Michael Coen, a former chief of staff at the agency. “These employees are usually the first boots on the ground,” he said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe agency has struggled with leadership turnover and the departure of experienced senior staff; FEMA has cycled through three directors in the past year. The agency’s current leader, Karen Evans, lacks relevant experience, Coen said.

Montano said rural parts of the country affected by a storm like this one typically need federal help more than urban areas. In places with smaller emergency management departments and fewer resources, “that extra support from the federal government is even more important,” she said.

Coen said he thought FEMA had done well so far coordinating with the states affected by the storm. “Hopefully the current Trump administration saw value in how FEMA coordinated and convened a meeting with 21 governors to talk about a national effort to ensure preparedness and how they would all respond together,” he said. Coen praised career staff at FEMA who have handled the response.

But he’s worried about future disasters. The effects of climate change mean that the next large-scale weather event may not be far behind this one. The agency has not said whether it will resume contract non-renewals after this storm has passed.

“FEMA is supposed to be ready for no-notice events. The current political leadership isn’t taking that into account, and they just react to storms as they happen,” Coen said. “For someone like me who has had a career in emergency management, that’s very troubling.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,