In the Northern California Bay Area, the weather has never pulled its punches. Storms pound the shorelines, king tides swallow streets and wind-driven wildfires blast through the forests. But the ocean and coasts in the region are bringing additional challenges, as rising sea levels push the waters of the bay higher and soil compaction sinks the land.

By 2050, according to a NASA-led study, sea levels in California are projected to rise between 6 and 14.5 inches above the average of levels recorded in the last quarter of the past century. During the next 25 years, Bay Area sea levels could increase even more, by over 17 inches, which would especially affect the city of San Rafael, in Marin County, one of the lowest-lying areas along the bay shoreline.

Due to the risks posed by the rising water levels, in 2023, the state of California enacted the Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plans (RSAP) to address sea level rise, build coastal resilience and support communities near the water. That initiative gave rise to the Sea Level Rise Collaborative Project (SLRCP) in San Rafael.

“Sea level rise in San Rafael, especially in the Canal area—a predominantly immigrant neighborhood that is home to more than 10,000 Latinos sitting on the ingress of the Pacific—is a big problem,” said Chris Cogo, an environmental justice specialist who is part of the SLRCP Steering Committee, a team made up of residents and property owners.

The city has seemed open to exploring just about every option for adapting to the rising seas, including expanding and restoring marshes, building living seawalls that support marine life as well as hold back the water, developing beaches of coarse pebbles and cobbles that prevent erosion and raising 2,000 feet of levees with ecotone slopes of plants to slow the velocity of waterflow. San Rafael’s sustainability program manager, Cory Bytof, said rumors that residents would be relocated from flood zones are false.

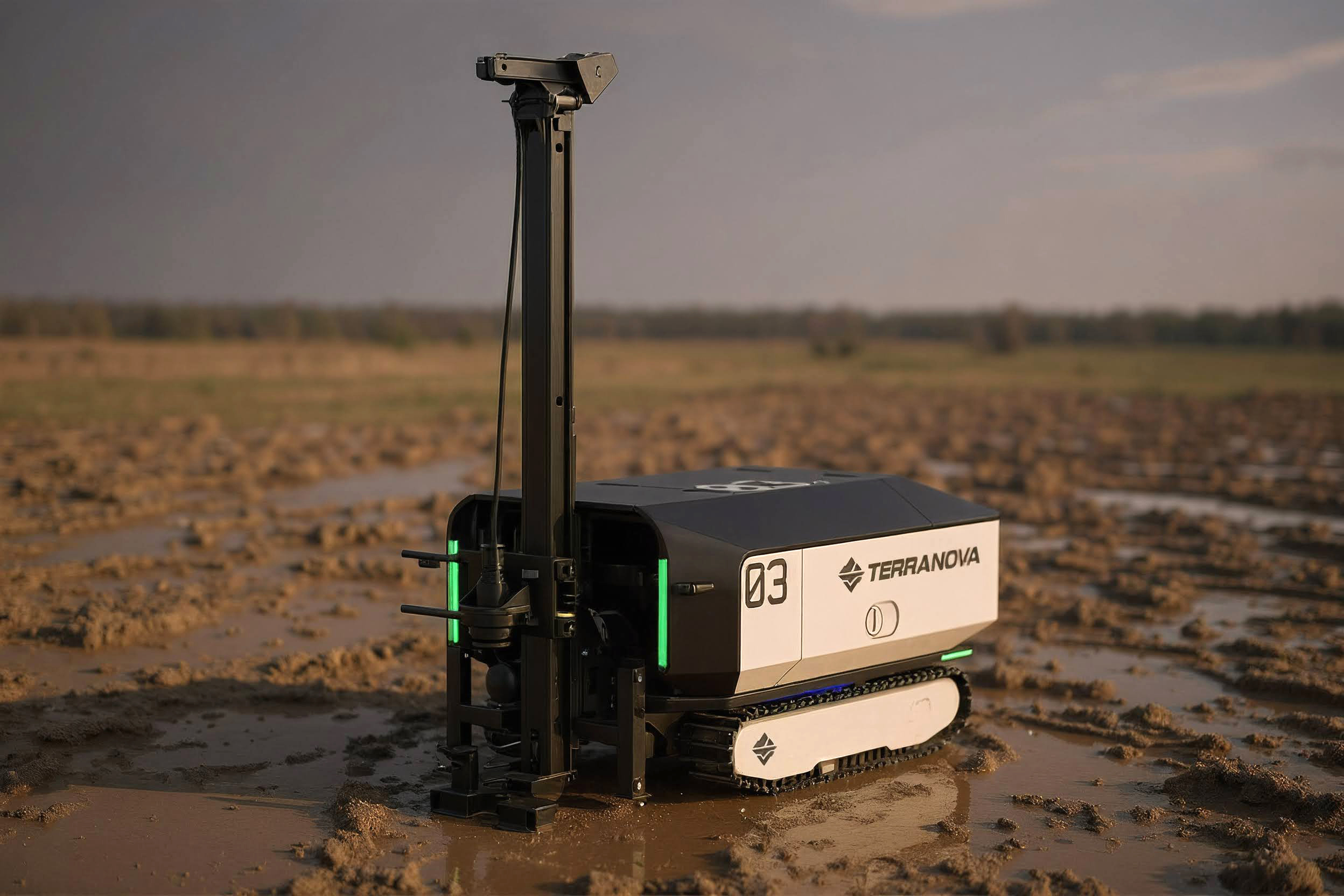

But another, more recent idea of using an AI-powered robot to raise sinking land in flood-prone zones has been met with skepticism from both city officials and residents who question its efficiency and long-term environmental effects.

The innovation known as land lifting involves drilling into the ground with a robot to form a crack, then pumping a mixture of wood chips, water and a thickening agent into the earth below.

“It’s like blowing up a balloon under a piece of paper. The surface—and everything on it—rises,” said Laurence Allen, co-founder of Terranova, a robotic flood prevention company proposing the strategy.

Raising Land and Sinking Carbon With AI

Father and son, Laurence and Trip Allen, San Rafael residents who co-founded Terranova, pitched the use of AI to hold back the rising seas to the SLRCP steering committee, at various times over the past year after meeting with a few city officials.

The process could also help slow climate change by sequestering the carbon held in wood chipped from tree trimmings and other aggregated sources, which are injected underground by the robot to raise the land. And credits awarded for sequestering the carbon could help offset the cost of the project, Terranova told the city.

Using machine learning models, the Allens said they have mapped out the underground geology of California from 700,000 data sets that show “red zones” at high risk of flooding. According to Laurence Allen, 40 years of geographical projections revealed that the entire downtown part of central Rafael and the Canal area would flood if nothing was done.

“So there are old sewage systems, old streets and old buildings that have sunk much more than the area around them,” Laurence Allen said. “You go into an area like that and re-level it, so bring it back to the level that it used to be at.”

Currently, Terranova estimates that about 240 acres of the most threatened areas in San Rafael would need to rise about 4 feet to compensate for past sinkage.

For $100,000 per acre-foot, the price the company quoted, it would cost the city $92 million to bury the 920 acre-feet of material the company estimates will be required to raise the sunken acreage. However, to maintain the integrity of the elevated areas over time, the city would need to inject roughly 12 additional acre-feet of material each year, which would cost about $1.5 million annually. Terranova believes that cost could be halved if Marin Sanitary, which collects biomass as well as residential waste, gathers and transports about 100 acre-feet of wood chips to the land-lifting sites each year over the course of 10 years.

And the company expects that much of the project’s cost could be subsidized by high-value carbon removal credits awarded for permanently sequestering organic waste, such as branches, leaves and chipped wood underground instead of sending it to landfills or incinerators. The credits can be sold to companies seeking to offset their emissions of greenhouse gases, subsidizing the cost of the land-lifting project to reduce the bill to city taxpayers.

Despite its environmental and financial potential, the company found the city wasn’t receptive to the innovation. Trip Allen called the resistance “Not Invented Here Syndrome.”

“Surely it’s smarter to bring in folks from the Netherlands,” he said. “Because how could it possibly be true that the best flood answer actually came from San Rafael?”

Official Skepticism

Kate Hagermann, Climate Adaptation and Resilience Planner for the city of San Rafael, expressed some reservations about Terranova’s new strategy. While she acknowledged that it is cost-effective, she questioned whether using AI engineering is the best route for the city when current and future infrastructural layouts are considered.

“For example, if we were to raise this building, how does it connect to the street? How does the street connect to the train tracks? How does the train get over the water? How does the train get under the highway?” Hagermann asked. “How does the highway get off of the, you know, off the off ramp?”

Rita Mazariegos, a SLR steering committee member and Canal resident working with a nonprofit focusing on the financial development of Latinos in the city, supports the idea of raising the land and said it would be too early to eliminate any proposals before the committee had fully considered and finalized a plan. She said her neighborhood, which “has flooded already once or twice, and people lose their things, you know, like they have lost cars,” needs immediate help.

Terranova said the San Rafael’s economic development office was “generally supportive” when the company approached the agency with the owner of the Canalways property (80 undeveloped acres near the San Rafael Target store).

“They told the landowner to submit a formal proposal to them with our technology,” he said.

Elevating land is not new to the Bay Area—much of San Francisco’s Marina neighborhood and part of the SFO airport sit on reclaimed coastal marshland and shallow water that was filled in. Land lifting, has in fact, been recommended by city leaders to help San Rafael adapt to sea level rise and land subsidence, so the Terranova founders were surprised the SLR steering committee didn’t jump on a partnership with the locally-developed flood prevention company, even after they had explained “our lower cost option extensively during the 8-10 meetings,” Laurence said.

Meanwhile, Cesar Zepeda, vice mayor of Richmond, California—a San Rafael sister city where the technology has received more support— said they are interested in “using local resources, local people and locally developed engineering to protect low-lying areas right away instead of waiting decades to see any protection from more complex and vulnerable levees and pumping systems.

“Simple, local and low-cost elevation seems to be a safer bet for our people,” he said in an email to Inside Climate News.

But Brian Snyder, associate professor of environmental sciences at Louisiana State University, whose work focuses on energy, carbon capture and climate change, cautioned that any land injection must be guided by detailed geologic information and consider seismic tests and previous land uses.

There have been no significant leakage or environmental effects from land elevation so far, the professor noted, but, in earthquake-prone regions like California, the process risks activating geologic fault lines. “There’s a big unknown there,” he said.

Elevating the land is not a one-size-fits-all strategy, Snyder said, but “at best a tool in the arsenal” that has not presented any adverse effects so far. However, it could pose environmental challenges in the future. The decay of woodchips underground would likely produce methane, a potent greenhouse gas, which could escape through fault lines. (Terranova claimed there was zero chance of this occurring if the slurry was kept anoxic, without any exposure to oxygen.)

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“Based on everything we know, this should be a safe process that removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and can potentially lift the land a little bit,” he said. “But, you know, in everything there is always going to be risks.”

In the meantime, in severe inundations, two main access points and escape routes from San Rafael—U.S. Highway 101 and Interstate 580—will flood.

“People don’t know where to go because there is no specific plan from the city,” said Mazariegos.

The city is still working with the residents on a feasibility study to identify potential interventions, said Bytof, the sustainability program manager, but so far, only moving the population is off the table.

“Relocation is not an option for analysis at this time,” he said.

The city expects a draft of the study to be completed sometime in the next month, Hagermann said.

San Rafael’s Two-Pronged Threat

Melting glaciers and ice sheets, as well as the thermal expansion of warming ocean water, drive sea level rise, which has led to severe flooding events in San Rafael. Between 1950 and 2016, the city experienced 19 flooding events that were declared federal and/or state disasters.

To make matters worse, NASA research shows that Bay Area cities, including San Rafael, have been sinking at a steady rate of more than 0.4 inches per year over the past 50 years as a result of sediment compaction that occurs when years of accumulated soft layers of earth such as mud, sand and clay are compressed by the weight of development on top of them.

According to the Multicultural Center of Marin, a community organization partnering with the city to address the threat of sea level rise, San Rafael has sunk 3 to 4 feet, which Terranova reports its data confirms.

The rate of global sea level rise has more than doubled in recent decades, increasing from 0.06 inches to 0.14 inches annually, an increase that was particularly steep between 2006 and 2015. This acceleration, combined with land subsidence, has heightened the risk for 270 properties in San Francisco, and more across the nine surrounding counties, where 13,000 properties, which are valued at $8.6 billion and house roughly 33,000 people, would be at risk by 2045, a 2018 study by the Union of Concerned Scientists revealed.

During this time, more than 2,000 homes in San Rafael are projected to be at risk.

In 2024, the county allocated $519,000 to support the SLR collaborative with the pool of funds coming from three principal funders: the Marin Community Foundation, the California State Coastal Conservancy and the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research.

Climate Funds Trumped

“Developing these plans is a big expense,” said Rylan Gervase, director of legislative and external affairs at the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), a state agency that leads regional planning for sea level rise in the Bay Area.

The Bay needs to spend $110 billion adapting to sea level rise, Gervase said in an email to Inside Climate News. “And the risk if we don’t is that we’re going to potentially suffer over $230 billion worth of damage.”

But it is reasonable to assume that efforts to address sea level rise will be affected by the current administration’s cuts to funding for climate and environment programs, the director said. Since President Donald Trump began his second administration, agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a primary source of climate science and data, have seen significant staff and funding cuts.

AI solutions for sea level rise are worth considering, Gervase said, but there are also tradeoffs between different approaches. The decision to adopt or reject any technology or approach is still at the discretion of a city, he said, as the BCDC does not interfere with the Shoreline Adaptation Plans.

Although elevating land is one of the adaptation strategies recommended for San Rafael, “it’s a lot easier to build from scratch than it is to go back and change an existing city,” said Hagermann, the city’s climate adaptation and resilience planner.

The local founders of Terranova, however, see a need to act with urgency.

“My hometown, it’s like $1 billion in flood damage a year-ish. It’s pretty ridiculous,” said Laurence Allen, of Terranova. “The city has flooded to like waist-deep three times now.”

Corrections: In a previous version of this story, the photo caption showing Terranova executive chairman Trip Allen giving a tour of the company’s facility mis-identified the group he was hosting. The tour was for the California state treasurer and her entourage, not venture capital investors. An earlier version of the story also misreported the amount that San Rafael has sunk. The city has sunk 3 to 4 feet, not 3 to 4 inches.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,