ASHEBORO, N.C.—Boxy, gunmetal gray buildings loom over a labyrinth of ducts and tubes and catwalks, beyond which 100 train cars loll on their tracks. Smokestacks wait to exhale.

This is StarPet, a mammoth factory in north Asheboro that manufactures PET polymers, derived from fossil fuels and used in polyester fibers and plastic bottles.

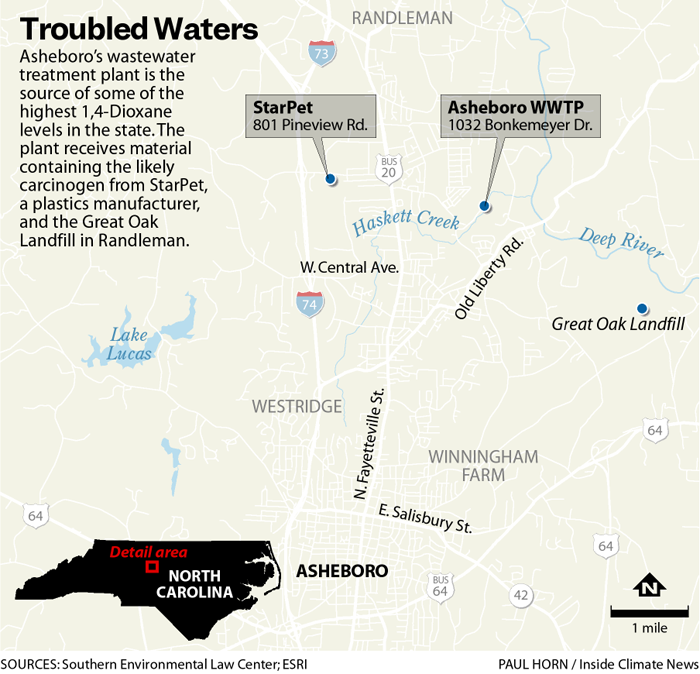

The facility lies a little more than two miles from the Asheboro wastewater treatment plant, a destination for StarPet’s discharge that contains 1,4-dioxane, a chemical designated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as a likely carcinogen.

Two environmental nonprofits, Cape Fear River Watch and Haw River Assembly, are suing the city of Asheboro and StarPet, alleging they have illegally discharged 1,4-dioxane and contaminated drinking water supplies for 900,000 people downstream.

“Asheboro and StarPet have an obligation to prevent this type of pollution from entering the environment,” the lawsuit, filed June 3 in federal District Court, says. “The defendants’ industrial pollution has devastating consequences.”

The Southern Environmental Law Center is representing the plaintiffs.

The city of Asheboro and StarPet declined to comment on pending litigation. In separate legal filings, Asheboro argued the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) didn’t have the authority to impose a numeric limit on 1,4-dioxane in the city’s wastewater discharge permit.

The new lawsuit is the culmination of a protracted struggle by state regulators, environmental advocates and downstream utilities to persuade Asheboro and StarPet to curb their discharge of the chemical.

Although the EPA has not established drinking water standards for 1,4-dioxane, it has set a health advisory goal of 0.35 parts per billion. North Carolina has similarly determined the chemical is toxic and poses a cancer risk above that level in drinking water.

The Clean Water Act requires municipalities to ensure their industrial users control their discharge before it reaches wastewater treatment plants. In North Carolina, DEQ regulates the municipalities, which in turn regulate their dischargers, such as StarPet.

Downstream water utilities, including the Fayetteville Public Works Commission, have begged Asheboro to stop besieging them with random slugs of 1,4-dioxane.

“The Upstream Dischargers,” which include two other cities,“wish to make 1,4-dioxane someone else’s problem,” the utilities wrote in a separate legal filing. “The problem is that there are real people who live downstream.”

What Is 1,4-Dioxane?

1,4-dioxane is a clear liquid, primarily used as an industrial solvent. It can be created as a byproduct of several manufacturing processes, including PET plastics. The chemical can also be found in soaps, detergents, textile dyes, paints and antifreeze.

Last November, the EPA issued its final risk evaluation for 1,4-dioxane and found it presents an “unreasonable risk of injury to human health.” The EPA has classified the chemical as a likely carcinogen. Long-term exposure to 1,4-dioxane can damage the liver and kidneys, and when inhaled, the sinuses.

EPA has issued a health advisory level of 0.35 parts per billion in drinking water, but there is not a legally enforceable federal standard for the chemical. Conventional treatment systems can’t remove 1,4-dioxane from drinking water.

Asheboro’s and StarPet’s refusal to rein in their discharge has been enabled by conservatives on the state’s Environmental Management Commission and the Rules Review Commission as well as an administrative law judge. All of these parties have stymied environmental regulators’ attempts to include 1,4-dioxane limits in Asheboro’s discharge permit.

SELC’s lawsuit asks a federal judge to rule that Asheboro and StarPet have violated federal environmental law and to force them to stop illegal discharges of 1,4-dioxane. SELC is also asking for the court to assess civil penalties and to require the defendants to cover attorneys’ fees.

“The polluters have definitely dug their heels in,” said Jean Zhuang, senior attorney with SELC. “These wastewater treatment plants should be asking their industries what they’re sending, and then regulating them.”

North Carolina’s 1,4-Dioxane Problem

Few people, if anyone, knew the extent of North Carolina’s 1,4-dioxane crisis until 2013, after the EPA included the chemical as one of 28 on the Third Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule. Public water systems nationwide began testing for the chemicals over 12 months.

North Carolina’s results were astonishing: The state ranked third in the U.S. in concentrations of 1,4-dioxane in drinking water, and fourth in the number of affected drinking water systems.

The EPA’s risk assessment concluded that North Carolinians are exposed to 1,4-dioxane concentrations that may be more than double the national average in drinking water and as much as four times the average in surface and groundwater.

NC State University scientists and DEQ sampled surface waters to pinpoint the source of the contamination. They found hotspots downstream from wastewater treatment plants in Asheboro, Greensboro and Reidsville, which discharge into the Haw River, Deep River and several tributaries to drinking water supplies.

In Asheboro, according to the lawsuit, there are two known sources that send 1,4-dioxane to the wastewater treatment plant: StarPet and the Great Oak Landfill, five miles away.

Great Oak has the highest levels of 1,4-dioxane in its leachate of any landfill in the state, according to court filings. It accepts contaminated sludge from Asheboro’s wastewater treatment plant, which then seeps into the landfill’s leachate system. The landfill then ships the tainted leachate—as much as 42,000 gallons per day, according to the lawsuit—back to the wastewater treatment plant, in a vicious cycle of contamination.

Waste Management, a private company, operates the landfill. It is not a defendant in SELC’s lawsuit.

StarPet has been owned by Indorama Ventures, a global company based in Thailand, since 2003. Its discharge permit, issued by Asheboro, allows the company to send as much as 70,000 gallons of effluent each day to the wastewater treatment plant.

Asheboro allegedly knew StarPet was discharging high levels of 1,4-dioxane into the city’s wastewater treatment plant as early as 2015, according to court filings. Since conventional water and wastewater treatment systems can’t remove 1,4-dioxane, the chemical flows from StarPet, through the city’s plant and dumps directly into Haskett Creek.

Since 2020, when city officials began sampling StarPet’s effluent, Asheboro has discharged high levels of the chemical into the creek at least 226 times, according to the city’s sampling results cited in the lawsuit.

Accounting for dilution, DEQ told the city three years ago to keep concentrations below 21.58 ppb to ensure levels downstream don’t exceed the EPA’s health advisory goal. The city allegedly has exceeded that benchmark 159 times, according to Asheboro’s own sampling results that are cited in the lawsuit.

Over the past five years, StarPet’s effluent has contained concentrations as high as 375,000 parts per billion, according to city data included in court documents. Levels that high caused Asheboro to discharge 1,4-dioxane at 3,520 ppb, court records say, 163 times the concentration allowed in its permit.

“Asheboro’s 1,4-dioxane pollution is a substantial contributor to this drinking water crisis,” the lawsuit says.

StarPet did install a pretreatment system for 1,4-dioxane in November 2020, but it frequently fails and is shut down for maintenance, according to the lawsuit. The system has gone offline six times since 2021, and twice since the beginning of the year.

Every time this happens, the lawsuit says, levels of 1,4-dioxane spike at the wastewater plant and downstream.

In January, StarPet shut down the system for two weeks, but its manufacturing and 1,4-dioxane discharges continued, according to court filings. Meanwhile, at the Asheboro plant, concentrations of the chemical in discharge reached 3,500 ppb, which was then released into the creek.

Failed Attempts to Regulate 1,4-Dioxane

Just three years ago, DEQ was on the verge of pushing through a legally enforceable rule for 1,4-dioxane in surface water. Environmental advocates and downstream utilities felt cautiously hopeful. Nine of the 15 members of the state Environmental Management Commission had been appointed by a Democratic governor, with the minority by the Republican legislative leadership.

The panel approved a standard of 0.35 ppb in surface water that is a drinking water supply, in concert with the EPA’s health advisory goal, with 80 ppb for non-drinking-water supplies.

The fiscal note, required as part of rulemaking, was complete. The final hurdle was the Rules Review Commission. The 10-member body, appointed by the Republican-majority legislature, reviews the administrative aspects of the proposed rules. Statutorily, the commission can’t consider the content of a rule, only ensure it is administratively complete.

Asheboro and other 1,4-dioxane dischargers objected to the standards, saying they were too expensive to comply with and that DEQ had overstepped its authority. The Rules Review Commission sided with the dischargers. The proposed standards were dead.

In 2023, DEQ saw another opportunity to rein in Asheboro’s contaminated discharge. The agency placed a limit of 21.58 ppb—accounting for dilution, the amount that would protect downstream drinking water supplies—in the city’s discharge permit, which was up for renewal.

Again, DEQ confronted strong political headwinds. Asheboro filed a contested case in the N.C. Office of Administrative Hearings. The city argued DEQ could not use a “narrative standard” to calculate and impose a numeric limit on its 1,4-dioxane discharges.

For nearly 50 years, state regulators have done just that: used a narrative standard to set and calculate numeric limits for contaminants in rivers, lakes and streams that otherwise don’t have such thresholds.

The narrative standard establishes methods to calculate contaminant levels to “ensure the concentration of toxic substances, alone or in combination with other wastes,” doesn’t harm public health or the environment.

The cities of Greensboro and Reidsville joined Asheboro in the case. They argued in court filings that Asheboro’s discharge limits could cause those municipalities to suffer similar “adverse consequences.”

“Together these polluters have systematically attempted to dismantle DEQ’s authority to regulate 1,4-dioxane and other harmful chemicals across the state,” the SELC lawsuit says.

Chief Administrative Law Judge Donald van der Vaart, a former DEQ secretary under a Republican governor with a reputation for weakening environmental regulations, assigned himself the case. Last year he ruled in favor of the dischargers, determining that the agency had exceeded its authority. The ruling voided the 1,4-dioxane limits in Asheboro’s permit.

After van der Vaart’s ruling, Asheboro allegedly allowed StarPet to increase its 1,4-dioxane pollution, according to the new lawsuit. “Consequently, levels of the chemical in Asheboro’s discharges have skyrocketed to the highest levels ever documented from a municipal wastewater plant over the course of North Carolina’s decade-long fight against this water quality crisis,” the lawsuit says.

On Jan. 3, in the final days of the Biden administration, the EPA sent a letter to DEQ objecting to van der Vaart’s decision. Federal officials noted that the limit “appears reasonable and consistent with the requirements [of the Clean Water Act] and may be included in the permit.” Unless DEQ submitted a revised permit containing the original limits to the EPA, federal officials said they would issue the permit instead.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowSince President Donald Trump’s inauguration, the EPA has taken no further action on that.

This spring, DEQ tried again, proposing the standards before the Environmental Management Commission—only now, the panel is controlled by Republicans. The commission rejected the agency’s proposal, opting instead for a “minimization plan” that would place no limits on the discharge and would take years to implement.

“That rule doesn’t actually require any reductions,” Zhuang told Inside Climate News. “It’s obviously terrible for the state of North Carolina.”

1,4-Dioxane Is Ending Up in Drinking Water

All seven miles of Haskett Creek, including a segment that receives Asheboro’s wastewater, have been on the federal list of impaired waters for 27 years. Lack of oxygen, excessive turbidity—or cloudiness of the water—and elevated levels of copper and bacteria have made the creek inhospitable to aquatic life.

Just past the wastewater treatment plant, Haskett Creek drains into the Deep River, itself wounded by urban runoff, lawn fertilizers and industrial discharges as it sojourns southward from near Greensboro toward Sanford.

A year ago, Sanford and Pittsboro, in Chatham County, merged their utilities to form TriRiver, whose name represents the three rivers—Deep, Haw and Cape Fear—that converge to become the drinking water source for the region. This week TriRiver will expand to Siler City and greater Chatham County, adding more than 11,000 households to their customer base.

Holly Springs and Fuquay-Varina, two of the fastest-growing towns in the region, also plan to tap into TriRiver’s water supply.

Cassie Hack, spokeswoman for the town of Holly Springs, said the utilities it purchases water from “are required to adhere to state and federal regulations.”

However, there are no legally enforceable federal or state regulations for 1,4-dioxane. Because of van der Vaart’s ruling last year, Asheboro is operating under its 2012 discharge permit, which contains no provisions for 1,4-dioxane.

Over the past year and a half, Asheboro has discharged 1,4-dioxane into Haskett Creek nearly every week, state records show, at levels ranging from 2.6 to 2,300 ppb. Data for six weeks is not available because the city did not sample on those occasions.

Depending on volume of river water and the flow, it can take two weeks for a slug of 1,4-dioxane to travel the 43 miles from Asheboro’s wastewater treatment plant to TriRiver’s intake. If the river is full, then the chemical could be diluted before it reaches TriRiver. But if river levels are low or the concentration of 1,4-dioxane is high enough, then the drinking water could become contaminated.

TriRiver tests its finished drinking water, which has been through its treatment system, for 1,4-dioxane monthly, utility spokesperson Cameron Clinard said. The utility also receives alerts from DEQ when the agency detects elevated levels of the chemical in Asheboro’s wastewater.

Of TriRiver’s 26 drinking water samples, taken from September 2023 to April of this year, 12 contained concentrations of 1,4-dioxane above the EPA’s health advisory goal, testing records show. The remainder of the samples did not detect the chemical.

The utility’s highest level in treated drinking water was 6 ppb, 17 times the EPA health advisory level. That occurred last November, two to three weeks after Asheboro discharged 1,4-dioxane twice into Haskett Creek..

If TriRiver detects elevated levels of 1,4-dioxane, Clinard said, the utility “could temporarily pause our intake procedure and operate off our reserve water for more than a week.” The definition of “elevated” would fall to regulators, Clinard said.

“TriRiver would welcome more specific guidance that comes with more concrete limits and specific action steps,” Clinard said. “That would help provide clarity for both water utility operators and customers.”

As part of the Sanford facility’s expansion, the utility is adding special filters to remove PFAS, known as “forever chemicals,” from the drinking water. The Pittsboro water treatment plant already has installed a $3 million PFAS treatment system.

But TriRiver’s water treatment facility isn’t equipped with the advanced technology to remove 1,4-dioxane, Clinard said.

Due to TriRiver’s “typically undetectable levels of 1,4-dioxane and the high cost of the treatment process,” Clinard said the utility chose not to add the treatment technology, but could do so “in the future, should it be needed.”

Several technologies are available, including granular activated carbon filters or advanced oxidation processes, which can use UV light and hydrogen peroxide or ozone to break down the chemical.

The cost of a 1,4-dioxane treatment system varies, but the town of Hempstead, New York, which serves 120,000 customers, has reported needing at least $40 million to remove the contamination from its drinking water.

At TriRiver, the additional cost would be borne by ratepayers, Clinard said.

The utility has not directly communicated with Asheboro or StarPet about their discharges, Clinard said. “As far as possible solutions go, we believe source reduction to be the most efficient,” he said. “Keeping 1,4-dioxane out of our source water helps us provide the highest quality water to our customers without having to raise their rates to buy the technology needed to remove 1,4-dioxane.”

The federal court has yet to set a hearing date on the SELC lawsuit; the defendants asked for additional time, until late July, to respond in writing to the complaint.

On July 11, DEQ is scheduled to appeal in Wake Superior Court van der Vaart’s ruling voiding 1,4-dioxane limits in the wastewater permits. The same week, the EMC plans to consider a 1,4-dioxane minimization plan. It would require Asheboro, Greensboro, Reidsville and other known 1,4-dioxane dischargers to start developing a plan to reduce contaminant levels—although by how much is not specified—no later than December 2026, with full implementation by February 2028.

By that time, TriRiver will be providing 80,000 customers with drinking water. At current production rates, StarPet will have made more than 1 million tons of PET to slake consumers’ thirst for plastic bottles. And untold amounts of 1,4-dioxane will have flowed into rivers and streams.

“The Clean Water Act never intended there to be a loophole where an industry can just send their waste to a sewage treatment plant and they’re off the hook,” Zhuang said. “You have to be responsible for your own pollution, and it’s Asheboro’s responsibility to make that happen.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,