Even as the U.S. federal government rapidly retreats from science-based decision-making, adopts climate-damaging energy policies and disengages from international climate efforts, 46 American researchers have been chosen as authors for the upcoming three main global climate reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

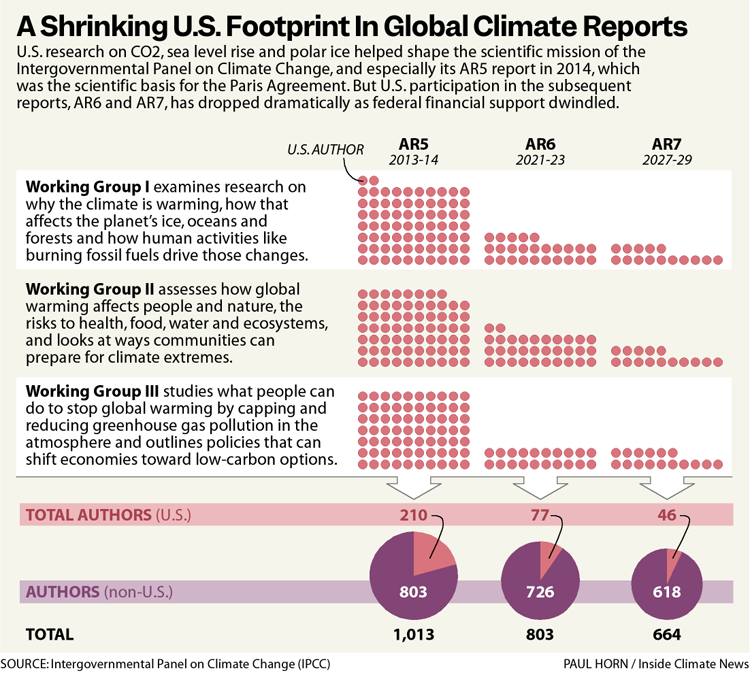

The number of U.S. scientists working on the IPCC reports has decreased markedly over the past decade, from 210 during the panel’s 5th assessment cycle to 46 in the current cycle, according to the panel’s records. But there are still more Americans or scientists with dual citizenship and U.S. university affiliations contributing to the reports than from any other country.

Former NASA chief scientist and senior climate adviser Katherine Calvin, whose role with the international panel was unclear after the Trump administration fired her from the federal agency, is among them. She will co-chair one of the three main assessment groups, IPCC Chair Jim Skea said last week.

“Kate is there and we see no route to her leaving that role in the future,” he said. Calvin, a climate modeling expert, made significant contributions to previous IPCC reports, he added, and will now help guide the structure and direction of the entire climate mitigation working group, with 222 scientists, including 15 other U.S. climate researchers.

The IPCC is the United Nations body responsible for assessing climate science and issuing reports every three to five years to guide government climate policies.

U.S. scientific agencies and their Earth observation programs from satellites were foundational to the IPCC’s earliest reports, in 1990 and 1995, as were U.S. ground- and ocean-based measurements of temperature increases, sea level rise and polar and mountain ice melt.

Measurements developed by U.S. researchers in Hawaii in the 1950s revealed a rapid, steady increase in heat-trapping atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, lending the IPCC’s work a sense of urgency since its establishment in 1988.

And it was a U.S. scientist who helped shape one of the IPCC’s most significant findings in 1994, when the panel concluded that the balance of scientific evidence “suggests a discernible human influence on global climate.”

The IPCC’s influence on global climate policy increased with its 2014 report, the scientific basis for the Paris climate agreement’s goal of limiting warming.

The IPCC has announced a total of 664 authors for the current assessment cycle. For the first time, there are more authors, 51 percent, from developing and emerging-economy countries than from developed countries. The percentage of female authors increased from 33 percent in the last cycle to 44 percent, bringing the IPCC closer to its goal of gender and geographic parity, Skea said.

“You’re seeing many more people providing strong scientific contributions from what you might call the emerging scientific countries, like China, India, Brazil, South Africa and Kenya,” Skea said. “They’re all coming through the system in much greater numbers, which can only be a good thing.”

In the context of the IPCC’s mission to synthesize global climate science, he also noted an increased proportion of scientific literature coming from Europe, China and India in recent years.

The first report in this assessment cycle on climate and cities is due in 2027, and there are five U.S. authors involved. Despite the lack of federal funding, they’ve been able to use philanthropic support to attend lead author meetings in person, rather than simply participating online, Skea said.

Strong Science Institutions Support Democracy

U.S. turnout for the IPCC is a sign that the science community is working to bolster institutional strength and resilience in the face of increasingly hostile political winds, said Rutgers University human-ecology professor Pamela McElwee, who helped coordinate the nomination process for U.S. scientists after the U.S. Department of State canceled the official federal process.

The drop in the number of U.S. authors for the latest round of IPCC reports can’t just be attributed to the lack of federal support, said McElwee, who will co-author a chapter in an upcoming report focusing partly on anti-science policies and climate disinformation.

“I’m not concerned about fewer U.S. authors, because it’s made space for other folks,” she said. “But I am concerned that the authors that were selected get support, and are not told by the federal government in any way, shape or form, what it is that they’re allowed to do.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowDespite the absence of the usual federal nomination process, the total number of U.S. scientists was as high as in the previous cycle, which was during the first Trump administration, thanks to an effort by 10 U.S. universities with official IPCC observer status and the American Geophysical Union, which presented a “nice united front” of scientific solidarity, McElwee said.

That effort included a web portal for nominations, established in late February and early March amid uncertainty about whether a federal nomination process would be in place before the IPCC deadline.

The U.S. science community is also organizing at other levels, including coordinating a response to a climate report issued by the U.S. Department of Energy several weeks ago, she said.

The AGU and the American Meteorological Society have also teamed up to publish a collection of papers to update information from a National Climate Assessment formerly compiled and issued by the federal government but canceled by the Trump administration.

Another group of international scientists is networking to establish independent, distributed systems for storing and sharing scientific information, specifically aimed at protecting science from authoritarian threats.

The threats come from oligarchs acting in their own financial self-interest and that of their political allies, which are often nationalist, populist and authoritarian parties and governments worldwide, University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann and Baylor University health researcher Peter Hotez write in a new book. “Science Under Siege: How to Fight the Five Most Powerful Forces that Threaten Our World” is scheduled for release in early September.

Such political actors spread disinformation on climate science and vaccine science, undermining public trust in science and government and threatening democracy itself, the scientists warn in the book.

“While it may be inconvenient to the current administration, the U.S. does have some of the leading climate scientists in the world, and they will continue to find a way to do and communicate the science regardless of the oppressive political regime,” Mann said.

Former IPCC member Richard Alley, an ice researcher and professor of geosciences at Pennsylvania State University, noted that scientists can spend hundreds of hours on IPCC work, and most of it is volunteer time.

“An IPCC report represents a lot of lost sleep and missed milestones at home while the scientists are laboring to put it together, while still continuing to teach, discover and serve in other ways,” he said.

McElwee said she sees both hopeful and troubling signs for science in the future.

International collaboration remains strong, with U.S. participation, and science is becoming increasingly global and inclusive of Indigenous knowledge, as well as doing more interdisciplinary work to identify the links between social and physical sciences.

On the other hand, the threats are very real, especially in the United States right now, she said, noting that the current administration has said it may rewrite existing reports that have met all scientific standards for accuracy.

That level of threat to scientific integrity calls for a strong response, and researchers in relatively safe positions with academic tenure should step forward first, she said.

Staying engaged in international scientific efforts and helping others do the same is her way of working to protect democratic norms. But she’s discouraged by watching the erosion of those norms.

“I’m increasingly looking at this and saying, what’s the point of being a scientist in a country that doesn’t have rule of law or doesn’t accept the truth of scientific experimentation,” she said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,